update:May 14, 2025

A special interview for the Toyota Foundation’s 50th year anniversary project

Efforts to tell and spread the stories of people suffering from chronic illnesses that are hard to be seen and understood -- Creating new concepts to understand the experience of chronic illness

Interviewed by Michi Kaga

Japanese text written by Nobuaki Takeda

Translated by Naoto Okamura

Japan, a country with one of the longest life expectancies in the world, is now said to be entering the age of 100-year-long life expectancy. This is a far cry from what the situation was like decades ago; Japan’s average life expectancy was 63.6 years old for men and 67.8 years old for women in 1955, 10 years after the end of WWII, according to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Advances in health and medical care are a big factor behind the increase in Japan’s longevity. This means that more diseases have become treatable. But at the same time, such progress in medicine has in turn made many illnesses more chronic, increasing the need for people to live with their ailments today.

In some cases, patients with chronic illnesses have to endure types of pain that are not easily noticeable to third-party persons and thus they have a hard time getting empathy from people around them, i.e., their chronic conditions make life difficult for them. The project granted by the Toyota Foundation in 2017 -- A Phenomenological Research Toward the Formation of New Concepts to Understand the Experience of Chronic Illness: A different perspective from medical cure or management -- was carried out, with the aims of deepening the understanding of their situation, paving the way for accepting diversity, and contributing to the building of an inclusive workplace and society.

Dr. Shiori Sakai, an associate professor at the School of Nursing in the College of Nursing and Nutrition of Shukutoku University, took the initiative to come up with new concepts (she was with Tokyo Metropolitan University at the time of the grant). In an interview with the Toyota Foundation, she talked about her thoughts about the grant-awarded project.

Details

- Program

- 2017 Research Grant Program

- Project Title

- A Phenomenological Research Toward the Formation of New Concepts to Understand the Experience of Chronic Illness: A different perspective from medical cure or management

- Grant Number

- D17-R-0563

- Grant Period

- May 2018 to April 2020

- Abstract of Project Proposal

- The progress of medical technologies has contributed to the decrease of lethal diseases. However, it has made a number of diseases such as cancers become chronic and has given rise to more people living with incurable illness which are different from "medical cure." New drugs and other technologies which may change treatments methods and people's lives are continually being developed. Thus an important feature of today's ill experience is that it is hard to foresee the future concerning possible (positive or negative) changes. We can no longer make sense of the diversified and complicated experiences from the existing perspective of medical management which divides them into "curable/incurable," or "disease/health." This study aims to form new concepts to grasp the way of living chronic illness through the approach of studying people with prevailing disease.

The results will contribute in (1) to nurture the socially required comprehensive abilities for health care professionals to examine and care for chronic patients, and (2) to build inclusive workplaces and society by cultivating readiness for more people to understand the lives of the chronically ill and to accept their diversity.

A reason behind her research – the suicide of a patient

In her own words, Dr. Sakai has described what the new concepts for understanding the experience of chronic illnesses are designed for. By and large, there are two objectives: the first one is to get a firm grasp of what it is like to experience chronic illnesses. At hospital, medical professionals often tend to focus too much on curing diseases or better supervising patients’ conditions, she said, adding that both medical care providers and patients themselves are led to believe that’s what they must aim for. “But in fact, there is another way of living for patients with chronic illnesses. Many chronic conditions do not become fully cured, and they need to learn to live with such conditions for a long time,” she said. “That comes with some difficulty. In recent years, there has been a lot of talk about experiencing difficulty in living. One of my objectives is to present an alternative perspective from the medical service side.”

The other objective is to build bridges across various fields, including academic and medical disciplines, so that a barrier-free workplace and society based on the understanding of living with an illness and diversity can be established in local communities and professional areas.

Such a concept originates from her tormenting experience as a nurse in which a patient of hers took his own life. Yet, this experience also prompted her to pursue a career in academic research.*1 “Upon graduating from college, I worked at a hospital’s neurosurgery department for five years. It happened in my third year,” she said. One of the patients Dr. Sakai was assigned to look after fell into a critical condition but he managed to recover. Later on, that patient recovered to the point where he could get back to work without motor paralysis or speech impediment, but some numbness remained in his left body. So, he got transferred to a hospital for rehabilitation but didn’t make much improvement. As a result, he would receive a treatment for easing the numbness at the anesthesiology department of the acute-care hospital where Dr. Sakai worked as a nurse.

Then, one day, she had a chance to meet that patient who came as an outpatient and was told that it was his last day for treatment at the anesthesiology department because not much improvement on his conditions had been observed. “He greeted me with mixed emotions on his face and said, ‘it was so good to see you, Sakai-san, one last time.’ I felt there was something strange, but I could not say much in reply and saw him off as I had other patients under treatment to attend to,” Dr. Sakai said. Then, a few days later, she received a call from the police and learned that the patient had taken his own life. “I was very surprised and shocked,” she said.

This left her drown in regret. Despite some lingering numbness as a result of a major illness, Dr. Sakai thought it was good that the patient had gotten better and become able to return to work. “In reality, however, that was not the case at all. It was totally different from what I had thought. The patient must have had an agonizing experience and difficulty, but I was not cognizant of that at all,” she said.

Since numbness is not a condition visible to the eye, people suffering from numbness are often seen as healthy individuals. Even if other people praised his efforts to recover from an illness and return to work, Dr. Sakai imagines that her former patient may have been feeling isolated despite having people around, which she thinks must have compounded his situation.

Finding value in the knowhow of people living with illnesses

In general, Dr. Sakai points out that academic papers invariably tend to focus on those people who make ideal recovery efforts. “Patients who make textbook-perfect efforts are viewed as great examples. For instance, those diabetics who cut down on rice consumption and do a lot of exercise are often presented in academic papers as something of ideal superman-like patients. But in fact, that must be tough on those patients themselves,” she said.

Indeed, not all patients can recover in such a superman-like manner. Meanwhile, there are those patients who manage to live with their illnesses in ways that are different than what the doctors think is ideal. There is one case in which a patient, while suffering more than 10 chronic illnesses including high blood pressure, diabetes, and hyperlipemia for 30 years, ended up not developing a major illness such as brain infarction. This is due to the fact that the patient was in contact with a hospital.*2 “Unlike a hospital-controlled treatment, this person learned to live well with illnesses for a long time in his unique way. “If patients can suggest (to doctors) that there should be another way, I felt that they themselves would be able to better cope with their conditions. What’s more, even though such an experience is precious, I felt that that kind of information rarely comes out publicly. My job is to find value in it and bring it out forth,” Dr. Sakai said.

While treatment of chronic illnesses is in principle “supervised” by hospitals, she said, quite a few patients cease to come halfway through due to the difficulty of their treatment. This means that they lose contact with the hospital and miss a chance to discover what can turn out to be a major illness.

An experience-sharing place “ikiiki (live well) café”

Japan will see a further acceleration of aging society, going forward. In other words, there will be more people suffering from chronic illnesses. “That’s all the more reason why I would like to tell people that there is an alternative way,” she said.

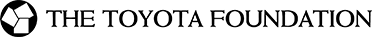

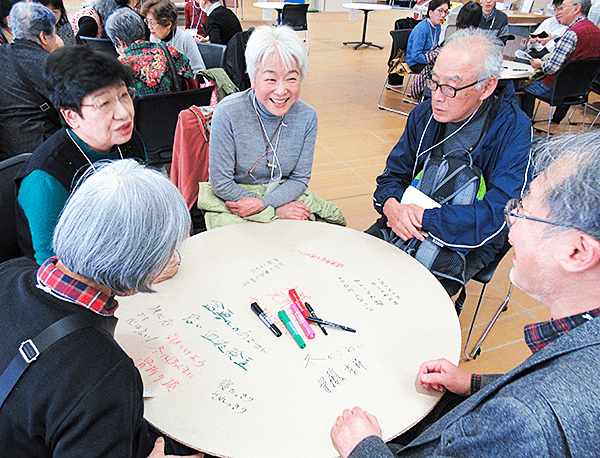

To help spread to society the concept of how to live with illness, Dr. Sakai has started holding a community café, called ikiiki (live well) café, in which people having suffered from an illness are invited as guest speakers to talk about their own experience for 15 to 20 minutes. After a coffee break, participants split into small groups of five persons or so to share their own illness experiences and listen to what others have to say. “I would like to give back to those who live with ailments in the local community,” she said.

Participants have suffered a variety of health problems including cancer, brain infarction, and depression. Some of them just want to brag about their health problems, while others simply want to talk about their illnesses. And there are those who just want to listen. “If we have a fixed group of members, that would make it more difficult for new people to come in. So, we change guest speakers every time and organize this event while trying to ensure a degree of flexibility,” she said. Initially, 5,000 flyers were distributed, but more people turned up at this café event than initially anticipated.

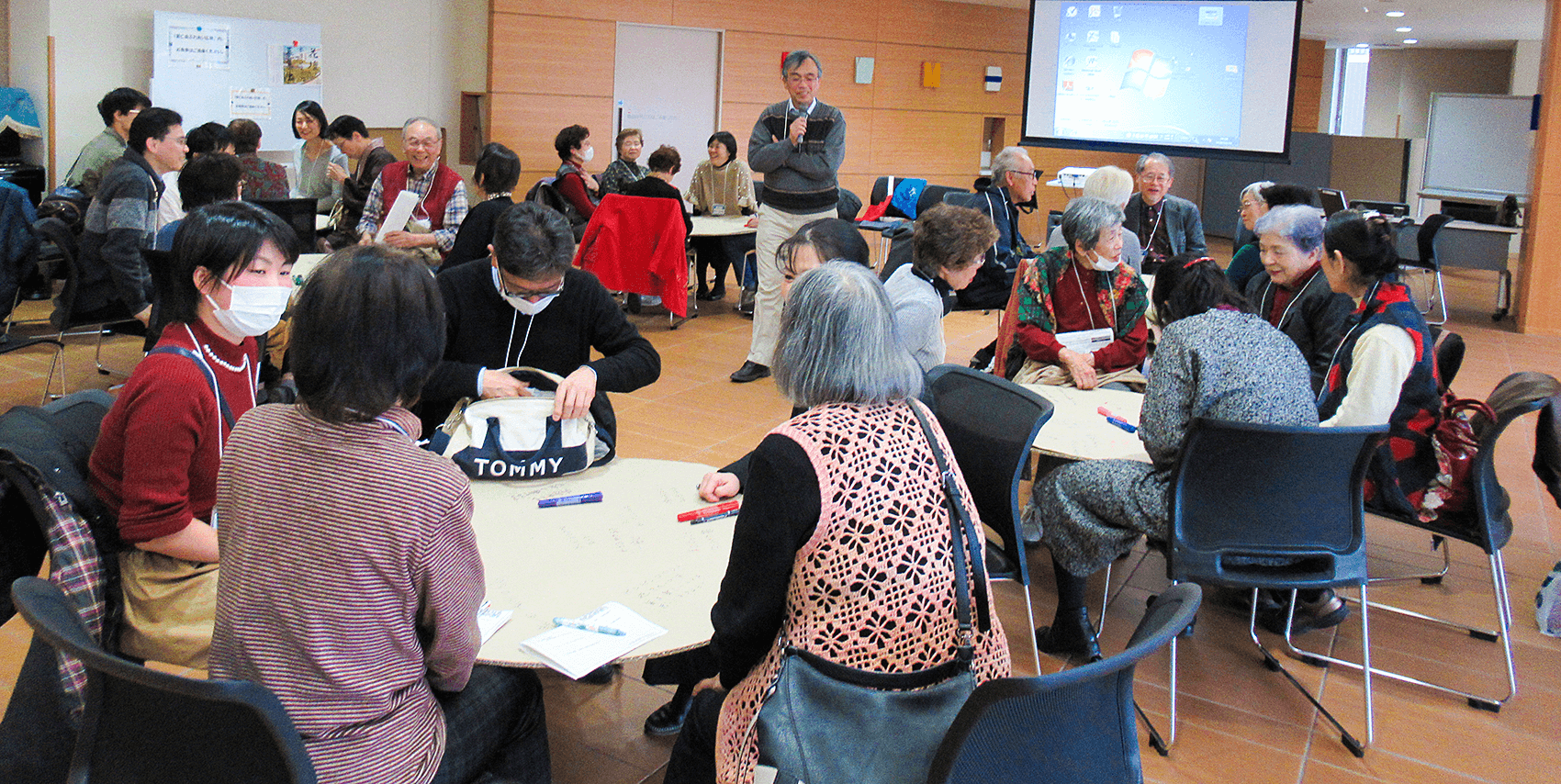

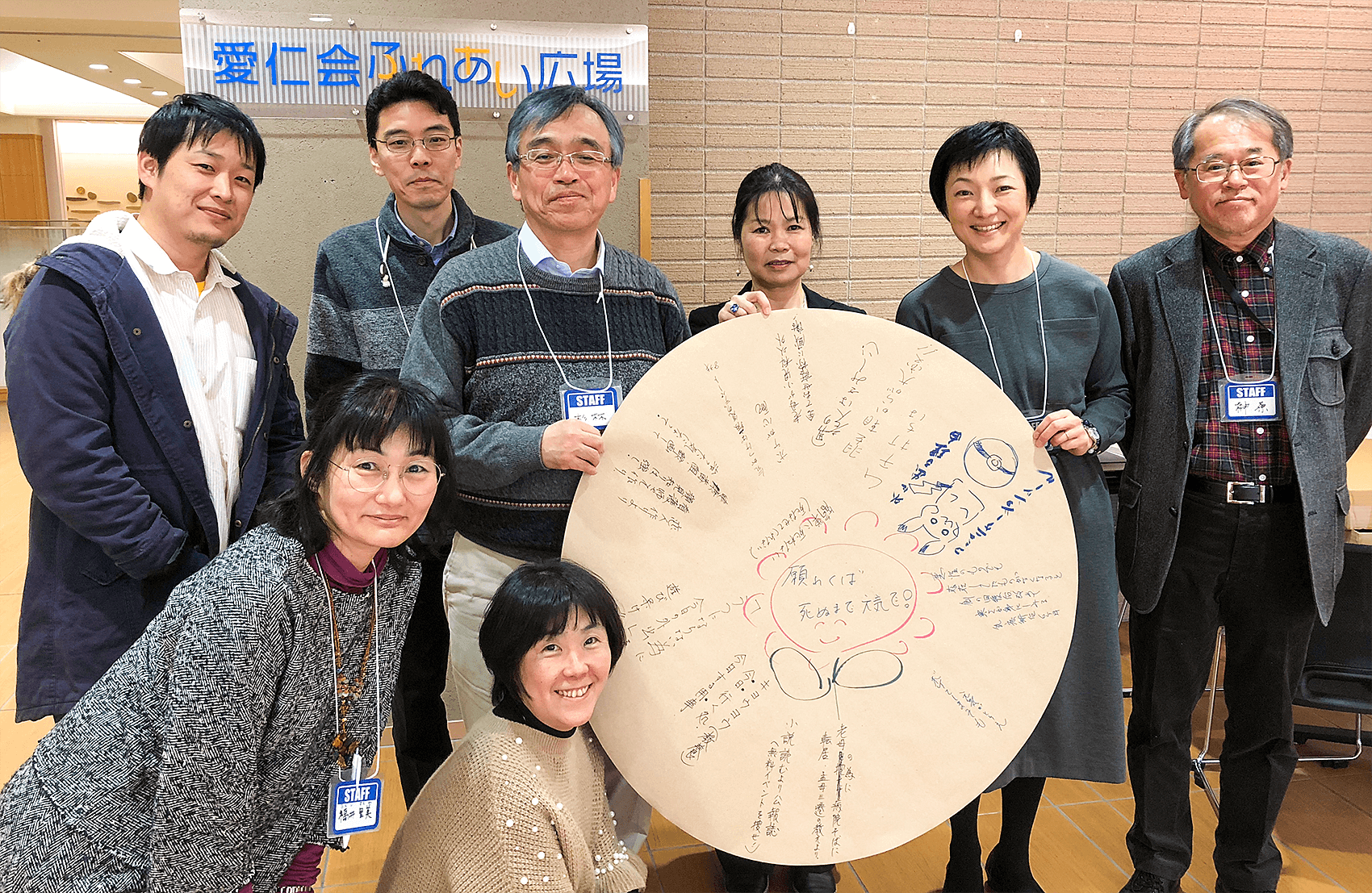

What is remarkable about this event is how Dr. Sakai and her team members conduct small group discussions. They employ round-shaped, feet-less carboard tables called “Entakun” (round table), and participants sit around them and talk to each other. One research member is assigned to each table as the facilitator, but other than that, participants are free to do what they want. Various people –participants who come on their own, couples, young and old alike -- took part. “They enjoyed talking to people they met for the first time, got to know people with different experiences, and found the event very refreshing. It has been well received,” she said. This is a good example that highlights the significance of sharing each other’s stories face-to-face, not via an online video meeting.

Creating a page-a-day calendar

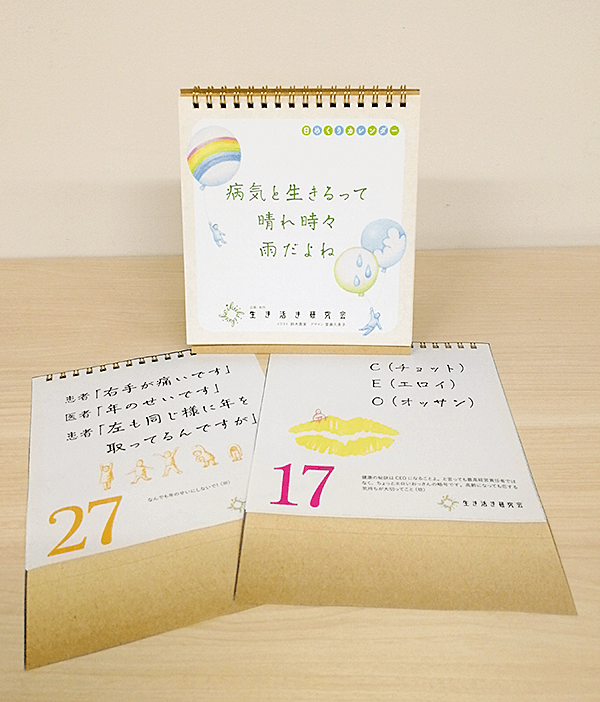

Sitting around this cardboard roundtable and talking to one another, Dr. Sakai said, participants produced a number of interesting words. Compiling them up would not be enough to make an academic paper, but she wanted to turn those words and phrases into a kind of tangible form. “Those words uttered by people living with illnesses were amazing, so I thought doing nothing about them would be such a waste,” she said. “Those words are about living with illness, so it needs to be something that can be used in everyday life and is not difficult to use, regardless of the season. One of our research members came up with the idea of a page-a-day calendar.”

There were a total of 466 impressive phrases that came out of 79 participants aged between 20 and 80 something, and 31 of those expressions were selected. As the calendar does not indicate January or the year 2024, it can be used repeatedly month after month and year after year. “We have included all kinds of words, positive, neutral, and slightly negative, and we have thought carefully about choosing which words to go into which date,” Dr. Sakai said. “Design-wise, vivid illustrations would not be suitable but graphics have to convey the meaning of those words. So, we proceeded with this project while talking closely with an illustrator.”

She told a story behind one such phrase on the calendar: Her pick is “the secret to health is CEO,” words by a senior woman living in the Kansai region. This “CEO” stands for a little bit erotic aged man in Japanese, she laughed. At a gym or a swimming club, an old man who comments on this woman’s new bathing suit seems to be healthy and active. “That’s why she told me that the secret to vitality was a little bit being erotic,” Dr. Sakai said.

Another interesting phrase on the calendar goes like this. “The patient: My right hand is painful. The doctor: It is because of your old age. The patent: My left hand is equally aging, too.” As such, this interesting page-a-day calendar is full of words and phrases that are quite relatable.

Initially, 500 copies were printed but they were all gone in just one day. A survey on customers’ feedback has revealed that a person suffering from an illness was given this calendar when she was feeling down due to a lack of improvement in her blood data, and she found some phrases that resonated with her. She left a comment saying “I was not alone and felt a little bit relieved.” It is good that the calendar serves as a vehicle for making a virtual connection with other illness-experiencing people whom calendar users don’t know personally, Dr. Sakai said.

“This project was not just done by researchers, but we were able to work with community members in producing this research outcome. We wondered about their needs and what they had on their mind, and worked together on creating this calendar,” she said. “Participants also felt it was fun attending the café event and good listening to other people’s experiences, and they felt a little lighter after talking. I find it significant that those small achievements leave a lasting mark in the heart of each participant.”

She also underscores the fact that the event proved to be encouraging to people living with illness, for it is not so common to talk about their illness to people outside of their family. “By sharing their experiences, they realize that there are other people like them, leading organically to the creation of an emotional space for encouraging and being encouraged. This is a huge discovery for me,” she said.

What’s more, Dr. Sakai wanted to bring this finding into an academic world. She invited a guest speaker to give a talk at an academic meeting, only to find that many researchers came and some couldn’t even find seats. “This gave medical professionals a chance to revisit the stereotypes they had. I think it was good that I was able to convey this value to a certain number of researchers,” Dr. Sakai said.

Spreading a new concept widely to society

This concept was not readily accepted in 2017 when Dr. Sakai received a Toyota Foundation grant, but she was able to gradually disseminate information about it to society through the page-a-day calendar and other activities.

The question now is whether her project has brought about any change in society. As their mission, many doctors put value on curing their patients. But, for instance, the Japanese Society for Chronic Illness and Conditions Nursing has increasingly been paying more attention to ways to live with incurable diseases. She feels that more medical practitioners think about what it is like to live with multiple illnesses, with more interest than before. “I will continue doing this work by producing academic papers and delivering speeches at academic conferences. When I look back five years later, 10 years later, or 20 years later, I would like to say in retrospect ‘we have come this far, but that’s how things were back then” and I think I am still halfway through to get there,” said Dr. Sakai.

In recent years, she believes it has become a challenge to let not just medical professionals but also ordinary people about this concept. Middle-aged and senior people are naturally prone to experience such health problems, but the challenge is how to get younger people more interested. “Young persons with chronic illnesses cannot talk about their conditions openly. As other young people around are full of vitality, they worry about receiving overly sympathetic reaction if they talk about their illness. So, they hide their conditions because they don’t want to be seen as being different or special,” she said. “My purpose is to turn our society into one where young people living with a chronic illness can just talk about it normally.”

The fact that they can’t talk about it seems to indicate how repressive Japanese society is. One such example is the prevalence of what is often referred to as the self-responsibility principle. “Be it falling sick or developing a chronic illness, it seems like people feel it is your own fault because of a failure to manage your own health,” she said. “You should manage your own illness properly while playing a role expected of you as a working adult. Responsibilities are only increasing, adding to more pressure on people living with illnesses.”

Dr. Sakai generated academic papers in order to break through that situation.*3 She worked with other research members in writing academic papers, arguing that an expression, “it can’t be helped,” should be seen and defined in a more positive light in research. “Instead of using it as words of helplessness, we can use that expression more positively as a way to forgive yourself,” she said.

Phenomenology-based practice (PBP) based on insights, not on numbers

Needless to say, Dr. Sakai’s research is ongoing. “As an evolved form of my research, I would like to shed more light on patients’ experiences, give such learnings back to society, and reflect them in the actual care-giving practice,” she said. But she also notes that practitioners argue that it is difficult to translate phenomenology research insights into an outcome. “I am now working on how to implement such an outcome,” she said.

For example, much of evidence, such as through evidence-based practice (EBP) or evidence-based nursing (EBN), is largely based on numerical values or experiments. In contrast, Dr. Sakai emphasizes that her research team would like to engage in practice based on revelations from phenomenology research, as opposed to EBP. “We would like to develop what we call phenomenology-based practice (PBP) and create a new type of care from the standpoint of a different value standard, which will be an evolution of our research so far,” she said.

Since PBP does not employ an easy-to-understand index in the form of numbers, it is quite challenging to spread the new concept of PBP. “PBP is different from quantitative research and numerical values obtained from examinations, but there is something that does exist. I would like to put much importance on how to incorporate that into practice as something meaningful. I would like to tell this method to various people,” Dr. Sakai said. “PBP relies on a new basis… and is not the same as natural science, so I would like to carve out a path that will lead to actual practice, at the very least.”

If academia moves to approve Dr. Sakai’s approach to creating value and developing a new research method with the members of a community, other researchers will likely follow suit and try to take on various initiatives in the future. At a time when calls for diversity are growing, new concepts such as hers, if approved and widely accepted, would clearly benefit society. She looks to continue doing her research for as long as it takes for her new-found concept to take root in society.

*1. Shiori Sakai (2019), Living with a numb body, Japanese Nursing Association Publishing Company.

*2. Shiori Sakai and Tomoko Hosono (2021), Study on the Experience of Living with Multiple Long-term Diseases that Lack Subjective Symptoms, No. 32-1, pp. 55-63, The Japanese Journal of Health and Medical Sociology.

*3. Minoru Sugibayashi, Michitaro, Kobayashi, and Shiroi Sakai (2020), A study on the experience of a mother and nurse suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, Vol. 3-2, pp.15-27, Journal of Clinical Phenomenology.