International

seikabutsu

Projects Outputs

update:April 17, 2023

◉ Raymond Hyma and Suyheang Kry Women Peace Makers, Cambodia

- Program

- 2018 International Grant Program

- Project Title

- Understanding "Us" to know "Them": Employing Facilitative Listening Design regionally to build empathy towards the Other through understanding those we can relate to

- Representative

- Suyheang Kry Women Peace Makers

Understanding ‘Us’ to know ‘Them’

A framework to question identity and association to “the other”

Five years ago, we sat together after finishing two projects about promoting understanding towards other ethnic groups in Cambodia. We began the work primarily based on strong anti-Vietnamese sentiment observed in Cambodian society. Given that the context was quite sensitive both politically and with the public at large, we began exploring it through a more multi-ethnic framework, connecting with diverse ethnic minorities, including the ethnic Vietnamese minority group. By including ethnic Vietnamese within a broader scope, we were able to take the spotlight off a single group and avoid the perception that we were overly focused on one group over another. Having worked with minorities in our city and in areas along the Cambodia-Vietnam border, we were full of reflections and thoughts about the future. Could we look beyond Cambodia and connect regionally to more deeply understand the phenomena we were studying? What if we extended our work into neighbouring countries Vietnam and Thailand?

At the heart of our work has been the action of “radical listening.” This form of listening requires you to put away all the filters that influence you to judge someone. Instead, it fosters the space for the speaker to be open, and for you to resist the temptation to respond with your own bias. To do this, you must first refrain from questioning with the purpose to challenge someone. The word “but” is a no-go. You also have to stop any judgements in your mind before they begin to shift how you are listening. This means avoiding the instinct to think about what you may have heard from others or even your own initial disagreement what is being said. Unlike what many people believe about active listening, it is not necessary to stay completely silent. Questions are encouraged, but you must really think about how you ask those questions and whether you can use them to make the person feel heard and more understood rather than challenging what they are trying to express.

Such listening can be uncomfortable for a listener. In fact, it’s one of the most difficult human actions to engage in, particularly between different people with very different perspectives. But how unbiased and neutral can one really be when exploring issues that matter to them? Can you really research topics that you are deeply connected to from your own lived experiences, in communities that might be the targets of such proposed research? Whether we can radically listen to something that we know very little about or we may know far too much about from one perspective or another, we will always come out of it with new information. Listening can provide us with deeper understanding and a fuller picture of the complexity of dynamics when studying the perceptions of different groups.

Over several years, we developed our own homegrown participatory action research approach in Cambodia known as Facilitative Listening Design![]() (FLD). FLD is a community-centred methodology that facilitates community members themselves to lead research activities including planning, data collection, and analysis on topics that are relevant to them. Community researchers, known as “Listeners,” reach out to subjects for their research who are referred to as “Sharers.” This is known as “insider” research. The Listener will normally be able to speak the same language as the community they are conducting FLD in. They may generally consider themselves as part of the community or identity themselves as the same. On one hand, insider research has many advantages in sensitive contexts. Insiders can often get more genuine data from those who trust them, who can communicate easily with them, and who can navigate the complex dynamics on issues that may be sensitive or less understood by outsiders. On the other hand, insider research is often seen as having more potential for bias or lacking the same neutrality as outsider research.

(FLD). FLD is a community-centred methodology that facilitates community members themselves to lead research activities including planning, data collection, and analysis on topics that are relevant to them. Community researchers, known as “Listeners,” reach out to subjects for their research who are referred to as “Sharers.” This is known as “insider” research. The Listener will normally be able to speak the same language as the community they are conducting FLD in. They may generally consider themselves as part of the community or identity themselves as the same. On one hand, insider research has many advantages in sensitive contexts. Insiders can often get more genuine data from those who trust them, who can communicate easily with them, and who can navigate the complex dynamics on issues that may be sensitive or less understood by outsiders. On the other hand, insider research is often seen as having more potential for bias or lacking the same neutrality as outsider research.

Facilitative Listening Design (FLD)

In FLD, Listeners are trained before they go back into their communities to conduct FLD conversations. During coaching and training, they go through many activities to not only learn the methodology, but also about more empathetic ways to listen. After several exercises to let them catch their own biases and realise how easy it is to interject in a conversation even when the focus is on listening, they are taught some FLD rules and provided with tips to ensure their FLD conversations will create the ideal listening space. They should begin by approaching people in their communities and assessing their potential to be Sharers. Before beginning the FLD conversation, Listeners must get consent from the Sharer, either orally or in writing. They should begin by talking about topics that might be most natural in any conversation. Does the Sharer have family? How long have they been living here? What do they enjoy doing after work? By using a natural way to get to know each other, they are then able to get deeper into the issues of focus of the FLD work. The Listeners are always instructed to never take notes or put any phones or devices on the table. They are encouraged to invite the Sharer for a coffee or tea, to help create a genuine conversational atmosphere. Conversations can be relatively quick (under an hour) or go on for much longer (several hours) depending on the flow and the wishes of both the Listeners and the Sharer. FLD always takes cue from the specific culture of the community. Therefore, it might be most appropriate to sit down in some cases or stand up in others. Eye contact may be important, or it might be avoided if deemed rude. During coaching and training, Listeners are asked to share their own cultural norms in communication and practice in trial conversations before they go out.

After and FLD conversation in the field, Listeners go off alone to note everything they heard in a template that is customised for them to record the data which is later presented and analysed in the full group. After a certain number of conversations (in this project it was after finishing four), the two Listeners analyse everything they heard, looking for any common themes across the conversations as well as any very unique points that might be brought up by a single individual. Eventually, Listeners bring all this data back to processing where they present it and do further analysis with the full group to identity and prioritise themes. FLD puts equal focus on the process as the findings, meaning that changes in perceptions by the Listeners themselves over the course of the research are seen as just as important through transformation that commonly happens when people listen to multiple points of view.

The team in Vietnam filming an ethnic Khmer dancer in Tra Vinh province.

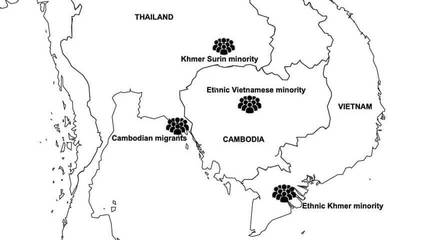

The choice of particular minority groups in this project was not haphazard. In Cambodia, the ethnic Vietnamese minority has long been seen with suspicion and as perpetual outsiders by the mainstream Khmer majority due to complex historical, political, and social factors. Their exclusion in society coupled with complex laws based on nationalistic views of citizenship and belonging have left many ethnic Vietnamese without clear legal identity or at risk of statelessness. We began with ethnic Vietnamese residents in a floating community that had been living there for several generations but mostly could not demonstrate clear citizenship neither in Cambodia nor in Vietnam. Not only did they live an isolated and marginalised life, but they were also seen with relative disdain by the mainstream Cambodian public and faced discrimination as "the other” in Cambodia. From there, we built our regional community. We looked across to Vietnam, where the ethnic “Southern” Khmer have been living in the Mekong Delta for centuries. Given the changing borderlines, when in 1949 that part of the former Khmer Kingdom was turned over to Vietnam, the sizeable Khmer population suddenly became a minority group. In Thailand, the ethnic “Northern” Khmer living in the province of Surin were similar, maintaining many aspects of their ancient culture and language. Their connection to modern-day Cambodia, however, was reduced centuries earlier after the fall of the Khmer Empire when in 1893 they were absorbed into the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand). These two minority groups outside Cambodia were seen positively by Cambodian Khmer, and even with a sense of nostalgia for a past kingdom in which Khmer across the region lived in unity. Although ethnic Vietnamese communities had been living in Cambodia for multiple generations, they continued to be seen as foreign immigrants by the mainstream. That influenced our decision to engage with Cambodian migrant workers in Thailand, many who had spent their lives as immigrants in their neighbouring country. All three minority groups outside Cambodia were seen as deeply connected to the Khmer mainstream and subsequently considered to some extent as “us.”

Through multiple activities and public events, the crux of this work was always to find out whether people could relate to who they considered “the other” by exploring how they saw themselves in different contexts. Like in many countries where people who are viewed as “different” or “foreign” reside, ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia have often been seen negatively by the mainstream. Many Cambodians would feel uncomfortable to hear them speaking in Vietnamese. There were often perceptions that Vietnamese in Cambodia were part of a larger plan to invade and infiltrate the country. But what about Khmer in Vietnam and Thailand? Would Cambodians be proud to see them continuing to practice Khmer traditions and culture? How about continuing to speak the Khmer language even after generations living in a country where the national language was different? The hypothesis was that if we could cultivate a pride in viewing Khmer minorities abroad, could we then foster more empathy towards minorities inside of Cambodia in preserving their own traditions, culture, and languages? In this case, if mainstream Khmer Cambodians could relate to ethnic Khmer in Vietnam and Thailand who live as minorities there, would they be able to then find any connection to the ethnic Vietnamese living as a minority in Cambodia?

FLD was the primary tool for mobilising minority groups together across borders around inquiry. Each group conducted FLD using the methodology they were trained in during their time in Vietnam. In total, they had 120 conversations in the three countries with members of their own minority groups. The space fostered between the Listeners and the Sharers during FLD conversations is very important. It allows everyday people from diverse communities to share their stories and reflect on their own thoughts and perceptions. In this case, being part of a minority group was one of the central focuses in the conversation. This allowed Sharers to conceptualise their own ideas of what their community meant to them, how they navigated life as a minority, and consider important aspects such as culture, language, and relations to other groups. Such a transformational space between the Listeners and the Sharers is crucial for both gathering information and providing the means for people to express themselves. One of the participants from Thailand noted that this space let them “hear the unheard,” particularly the minority groups that tended to be invisible in Thai society. This space in which knowledge can be generated among all those participating is not unrecognised in research. Many Indigenous qualitative methodologies embrace the co-creation of knowledge between researchers and participants that also leverage the knowledge of the researcher. Within FLD conversations, Listeners provided the space for Sharers to conceptualise their lives and convey their truths guided by the understanding that they also shared similar understanding and instinctive ways of knowing in their own communities.

The Listeners met again half a year later to process data and present results to all groups. This analysis phase was crucial in sharing their findings with other minority groups in addition to mainstream members from their countries who had coordinated activities. Listeners shared details from their communities without any interruption because they focused on their findings rather than expressing any opinions or reflections. Such a learning space is where real transformation and mutual understanding begins. Participants from all countries had their chance to present their findings, but more importantly, to listen to the findings of others. They heard and identified connections as well as differences. When asked directly what the Listeners believed could connect their Sharers across borders, they provided a range of answers: same way of thinking, language, culture, tradition, history, same group, community… When asked what connects “Us” together, each Listener had a chance to reflect both on their own community and on themselves: same goals, different people but the same human being, relationships, openness, understanding, humanness, acceptance, and shared values… In later reflection on the process of FLD after processing the data, Listeners also shared their own experiences implementing the methodology in their communities. For the most part, Listeners felt that FLD allowed them to more deeply connect to their own cultures and subsequently explore more inwardly into themselves. Several Listeners said they could learn more about who they were and where they came from by listening to members of their communities. One of the major outcomes of the FLD intervention was the fostering of a group that could more genuinely express their multifaceted identities and find themselves within each other. The minority layer of their identities connected deeply to one another and made borders irrelevant.

The team processes data and carries out analysis of their FLD research from across the region in Buriram, Thailand.

A second phase of listening took place via a different methodology – human-centred storytelling through the lens of a camera. Listeners who had previously conducted FLD were brought together and trained in filmmaking that involved humanising everyday people. They produced short films over three days in Phnom Penh with people they met in the street and were able to screen them to the public in that incredibly short timeframe. With new skills in leadership and filmmaking, they went back to their communities and produced additional short films to capture a story from one of the Sharers they had listened to in FLD. Their films explored the life of a member of their minority community and brought their FLD data to the big screen in a very different form for others to experience the dimensions of minorities, and even allow them to compare their own lives with them in a very human way (see Parallel Lives![]() ).

).

From a content perspective, we gained enormous new knowledge through findings from all communities. We learnt about pride in practising culture and traditions, desires to meet others across borders, and very particular challenges living as minorities in their countries. From a project perspective, we also learnt a great deal. Minority groups tended to transcend borders, were connectors across countries through culture and language, and held similar shared lived experiences. When bringing minority groups together in the different countries, a new space emerged that nearly appeared borderless. In that space, nationality had little meaning. Numerous languages were being spoken among Listeners, often mixing Khmer, Vietnamese, Thai, and English in the same conversation. Much surprise would suddenly be expressed when one group would find a similarity with another group. For example, the Khmer from the northeast of Thailand, would describe their ancient ceremonies to find out that the Khmer in southern Vietnam did something very similar nearly 800km away with two borders separating them. They would compare their languages, finding common words and concepts that they shared. The ethnic Vietnamese from Cambodia would equally participate, knowing Khmer culture from their mainstream exposure, and could also share the sense of being a minority within their country, where they were often made to feel like outsiders.

We also learnt from the mainstream participants that supported coordination. Although it was not initially by design, in-country coordination brought three mainstream participants into the work to ensure things went smoothly with their minority groups in each country. The accompaniment of mainstream participants alongside the minority participants was an unexpected transformational component. In one reflection session, a coordinator who was not part of a minority group said she felt like she became a minority in the project. She couldn’t speak the language many participants chose to speak to each other, couldn’t connect to different cultures in her own country, and couldn’t relate to being a minority herself like others. She told the group that she heard things from a minority group in her country that she had never considered before. This insight showed us that by bringing minorities together across borders as a group rather than designating them by country fostered a space where they could tap into several layers of their identity and connect on levels that far surpassed nationality. It also validated the attempt to reframe how people may view others and by putting them “in the shoes” of others in order to potentially cultivate deeper empathy towards “the other.”

This transformational dimension through the process of FLD did not only occur among the mainstream coordinators. The Listeners also expressed how FLD and human-centred storytelling filming impacted them while working with their own communities. A mixed ethnic minority Listener from Vietnam felt deeply changed after conducting FLD in Khmer minority communities in his country. Although fluent in Khmer language and knowledgeable about Khmer culture and traditions, the chance to engage in 40 conversations with community members made him re-evaluate his own identity. “I have been able to better understand my own Khmer heritage and identity, almost as if something had awoken in me from listening to others,” he shared when Listeners processed the data together. A Listener originally from Cambodia who had worked for years in Thailand with migrant workers also conveyed the major change he experienced while doing the research on Cambodian migrants in Thailand alongside his counterparts from Cambodia and Vietnam. At the book launch in Phnom Penh three years after the research, he told the audience how he had changed over the years:

I remember I used to think that the ethnic Vietnamese people or even Thai people living in Cambodia are not the same as me. Yet, through this work, I realise I can live with them as well. I have Vietnamese friends in Uddor Mean Chey province and even Thai people. We all can enjoy together. Vietnamese people in my community are friendly and always share food and drink with me ... I know how the migrant workers in Thailand feel like being mistreated, so how could I do so towards others back in my country? We are now being friendly towards each other. We can drink and play football together in the evening.

His reflection demonstrated that listening and looking beyond our contexts (in this case, looking across our borders and imagining ourselves in minority situations), it is possible to change our own perspective towards “the other” that we may have lacked empathy for at some point in our lives.

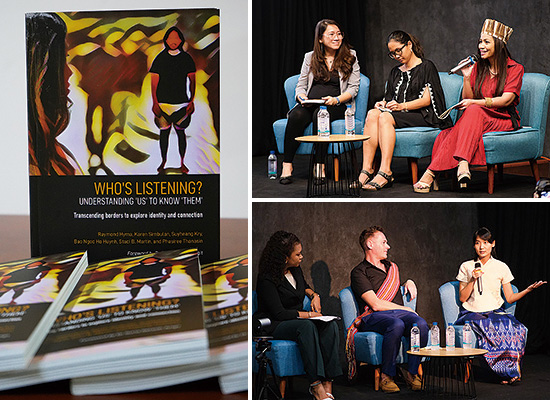

Book authors from Cambodia, the Philippines, and Malaysia discuss the publication at the book launch.

Book authors from Thailand and Canada discuss the publication at the book launch.

In the final phase, we connected with likeminded experts in our three target countries plus others from Malaysia, the Philippines, the USA, and found synergies with those working in Myanmar. Together we discovered that our concept, Understanding ‘Us’ to know ‘Them,’ was far more universal than the three countries we set out to focus on. Everyone seemed to be able to identify a group that they saw as “the other” in their own contexts. Whether it was those of a different ethnicity, nationality, gender identity, generation, religious belief, or ideology, it was almost always possible to find a subgroup or representation of oneself in that so called “other” group. With this group along with other members of our core group, we developed a reflexive writing process. This allowed us to bring out our FLD findings accompanied by the powerful insights of others in the region working on related issues and topics in order to situate our research into a wider context. The outcome was a piece of work deeply grounded in local minority communities in Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand, but with the outlook to extend to regional and even global audiences exploring the positionality of “the other” in their own contexts.

The experiencee garnered from this work and the tools produced through a range of outputs have contributed to wide-reaching dissemination throughout the duration of the project. The human-centred films produced by the Listeners were screened in Phnom Penh (see Screening and Dialogue![]() ) and in Vietnam and Thailand with communities who had been involved since the very beginning. These events leveraged film and visual storytelling for deep dialogue on issues related to minority communities in all three countries. Community artwork with the ethnic Vietnamese minority in the floating villages of Cambodia contributed to a stunning art exhibition in Phnom Penh that fostered multiple discussions on sensitive topics without specifically naming the communities. This not only provided a creative dialogue space, but also avoided any potential harm during a very sensitive period of forced relocation and public negative sentiment (see Life Afloat – A living exhibition of a community and a home once upon a time…

) and in Vietnam and Thailand with communities who had been involved since the very beginning. These events leveraged film and visual storytelling for deep dialogue on issues related to minority communities in all three countries. Community artwork with the ethnic Vietnamese minority in the floating villages of Cambodia contributed to a stunning art exhibition in Phnom Penh that fostered multiple discussions on sensitive topics without specifically naming the communities. This not only provided a creative dialogue space, but also avoided any potential harm during a very sensitive period of forced relocation and public negative sentiment (see Life Afloat – A living exhibition of a community and a home once upon a time…![]() ). A report on the same community using the data from FLD helped stakeholders to better understand the changing context and the situation that the minority community in Cambodia was facing (see A Community at a Crossroads

). A report on the same community using the data from FLD helped stakeholders to better understand the changing context and the situation that the minority community in Cambodia was facing (see A Community at a Crossroads![]() ).

).

By the end of 2022, we published and launched a comprehensive book on our work that not only tells our stories, but also challenges readers to apply this concept to themselves in perceiving “the other” (see Who’s Listening? Understanding ‘Us’ to know ‘Them’![]() ). We also produced the first cut of a film that retells the stories of minority groups across our borders and blurs characters and stories, showing the strong connection and similarities we share from one place to another. Where the Sun Sets is an ethnographic documentary that brings the concept of Understanding ‘Us’ to know ‘Them’ to audiences through stunning visual scenes and places in our region that connect minority groups and their “home” through its woven story collection. Beyond the project’s timeframe, this film is being produced into a Director’s Cut that will be taken to worldwide audiences to share our concept and learnings with others. All of this work has generated new knowledge and content that is being shared with high-level stakeholders, including UN agencies and key civil society actors, that are not only receiving data and numbers, but also very human stories and expressions that call for further action on issues of discrimination, exclusion, legal identity, and statelessness.

). We also produced the first cut of a film that retells the stories of minority groups across our borders and blurs characters and stories, showing the strong connection and similarities we share from one place to another. Where the Sun Sets is an ethnographic documentary that brings the concept of Understanding ‘Us’ to know ‘Them’ to audiences through stunning visual scenes and places in our region that connect minority groups and their “home” through its woven story collection. Beyond the project’s timeframe, this film is being produced into a Director’s Cut that will be taken to worldwide audiences to share our concept and learnings with others. All of this work has generated new knowledge and content that is being shared with high-level stakeholders, including UN agencies and key civil society actors, that are not only receiving data and numbers, but also very human stories and expressions that call for further action on issues of discrimination, exclusion, legal identity, and statelessness.

After working so intensely with minority communities to push the boundaries of identity and question who are “we” and who are “they,” we know this work needs to reach mainstream and majority communities. We have already seen that it can inspire others through the depth of stories coupled with art and data. It also has enormous potential to create wider alliances for action on many topics and issues. Our goal now is to not only bring together minority groups, but to put this concept into the mainstream in order to foster deeper empathy among them when they view “the other,” whoever that may be. The wonderful thing about identity is that it is not static. It is up to each and every one of us to turn “them” into “us” by more deeply analysing our own identities and finding a layer to connect to others that we may not have initially associated as being part of “our” group.